Cats’ meat men were in the pet food home delivery business during the 18th and 19th centuries and into the 20th century. We seem to have taken a backward step as even milkmen have all but died out in Britain. There were a lot more street vendors in London, England in times past than there are today. They would hawk their wares as the saying goes.

Henry Mayhew wrote about them in his record of London life: London Labour and the London Poor -Volume One (see an extract on Google). He worked out, from first hand interviews, the size, in terms of total financial turnover, of the various street businesses of his time. The book was published in 1861.

Sellers of cat meat to the public were mostly men and there were about 1,000 of them in London in the middle of the 19th century. Mayhew calculated that there were about 300,000 cats in London at that time. One vendor of cat meat estimated that “there’s a cat to every ten people, aye, and more than that”. If that is correct it gives us an insight into the numbers of domestic cats in the UK at the time.

Sellers of cat meat to the public were mostly men and there were about 1,000 of them in London in the middle of the 19th century. Mayhew calculated that there were about 300,000 cats in London at that time. One vendor of cat meat estimated that “there’s a cat to every ten people, aye, and more than that”. If that is correct it gives us an insight into the numbers of domestic cats in the UK at the time.

The percentage of cats to humans in 1998 was 13.24% in the United Kingdom. In other words there was about one cat for every 7.5 people in the UK in 1998. I conclude, therefore, that the domestic cat was as popular with British people in the mid-1800s some 160 years ago as at present (2012). I find that interesting. The general consensus is that the domestic cat population has expanded over the years, which it has, but only because human population has expanded. The human population of England and Wales in 1861 was 9.7 million. Today it is 55 million.

However, in those days the domestic cat sometimes lived a semi-feral life; certainly a much more open relationship with their human keeper. Of course, there were instances of very close relationships such as occurs today. Dr. Samuel Johnson’s home is an example. He loved animals and cats.

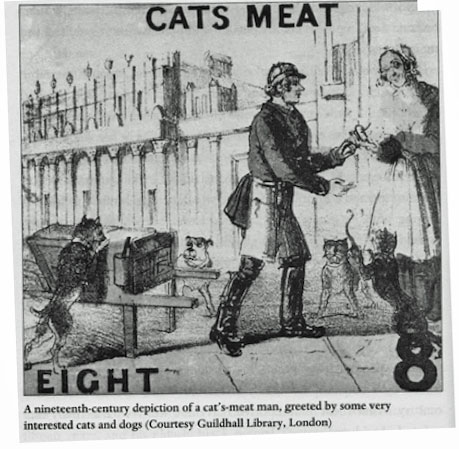

Cat’s meat men wore a sort of uniform which included a shiny black hat and a plush waistcoat! A blue apron and corduroy trousers were also part of the garb. They liked to wear a spotted handkerchief or two around their necks. The picture above should show this but I am not sure it does. I see the hat and apron though.

The meat they sold was horse flesh, freshly processed at the local knacker’s yard who started work in the late evening to supply meat in the morning. There were a lot of horses in London at that time.

Cats’ meat men called out as they walked down the street with their barrow and their horse meat on skewers: “Cat’s meat-cats’ meat, on a skewer come and buy”

The big problem which went unrecognised at the time is that pure, boiled horse flesh on its own is not a good, balanced cat diet. The mouse is the perfect diet and that means pretty much the entire mouse including stomach contents. Obviously the domestic cat supplemented the horse meat with rodents! There was no cat food as we now know it. Dr. Samuel Johnson who authored the famous dictionary fed his cat ‘Hodge’ with prime quality oysters as a supplement.

Although selling cat food was a good business, many becoming relatively well off, many customers bought on credit and some failed to pay. Some vendors such as Mr Cratchitt was a self confessed “man of independent means” on the back of selling cat food on the streets of London.

Profits were good for cat meat vendors making a net profit of up to one pound (£1) per day, selling up to 2 hundredweight of cat meat (cwt = 112 lbs). This is £43 at 2005 values. That would make it about £50 in 2012, I suspect. That would not make you a man of independent means today, nowhere near, so obviously living costs relative to earnings were much cheaper in 1861 or Mr Cratchitt had a team of vendors working for him. I think the latter was the case.

Note: the pictures have been deemed to be in the public domain due to the passage of time and expiry of copyright. Please inform me if I am incorrect in that assessment.