The origin of the scientific name of the sand cat is interesting. This cat species was discovered by Capt. Victor Loche in 1856 in eastern Algeria on a French expedition lead by General Margueritte. He named the cat Felis margarita after the expedition leader. Although at one time it was thought that this cat was the wild cat ancestor of the Persian cat, this is now considered incorrect. It is also called the “sand dune cat”. Its name is not to be confused with the “desert cat” Felis silvestris lybica, which is a subspecies of the African wildcat.

Sand cat – Felis margarita |  |

Appearance

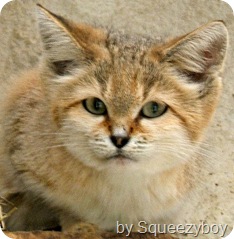

The photographs by Flickr photographers who kindly allow their work to be used under a Attribution 2.0 Generic creative commons license show the appearance of the cat. The sand cat has the appearance almost of a domestic cat albeit more muscular and obviously wilder looking. It weighs 2-3 kilograms (4.4 to 6.6 lbs). The average weight is in the order of 2.7 kg (6 lbs). This is on the medium to light end of the domestic cat scale of weighs (see largest domestic cat breed).

Camouflaged beautifully for sandy conditions with a pale sandy coloured tabby coat, the face is noticeably broad and the ears large set on the sides of the head (compared, for example, to the Serval and Serval Cats – opens in new window). The face is both sweet, wild and a little aggressive looking at the same time. In fact, the skull shape is an adaptation to desert life and is similar to that of the manul ,with large eye sockets and a “bulging brain case” (Wild Cats of the World). The skull contains a hearing structure, the bony covering of the middle ear called the tympanic bulla, that is enlarged and which is thought to be an adaptation to increase low-frequency hearing. The large ear flaps (pinnae) support excellent hearing too. Hearing is important in locating prey in the desert.

RELATED: See a page on the adaptations of the sand cat to desert life.

Although the markings are very faint there are strong stripes on the forelegs. The density of the coat colour fades to off-white on the undersides. The fur is dense and makes this cat looking larger than it is. Its well camouflaged body allows it to hide very effectively when threatened by crouching low to the ground besides a rock with its chin touching the ground and ears flattened to mimic the rock.

An interesting feature of this cat is the thick fur that grows between its toes, which protects the pads of the paws against the hot sand of the desert. Apparently, they encounter very cold conditions too, so the fur insulates against cold as well. The Black-footed cat is similar in this way.

The Sand cat can move fast when required but its short legs mean that it moves close to the ground.

Where do we find the Sand Cat?

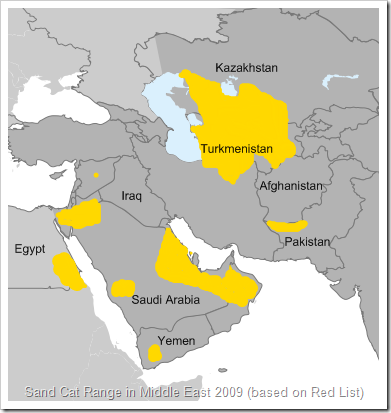

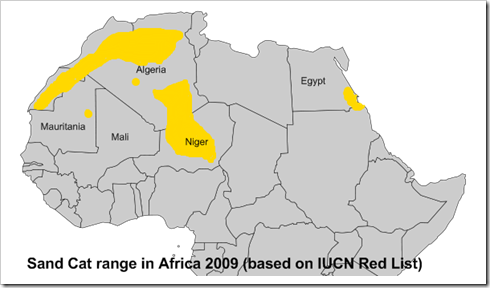

At 2009, this wild cat is known or believed to occupy: Algeria, Iran, Jordan, Niger, Pakistan, Syria, Turkmenistan, UAE, Uzbekistan, Yemen (see photo), Oman, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Egypt, Mauritania, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, W. Sahara, Israel.

It may also occupy the following countries: Tunisia, Libya, Qatar, Chad, Mali, Afghanistan, Senegal and Sudan.

However, it should be noted (see immediately below) that there is not enough information on the distribution of this cat to be able to say that the above maps are truly accurate.

Update: 30-9-09 – Below is a map of the Sand Cat Range that can be refined by anyone who knows better. It is based on the IUCN Red List map:

View Sand Cat Range 2009 in a larger map

Threats and Conservation – the status of the sand cat in the wild

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ classifies the sand cat as Near Threatened as at 2009 but reclassified more generously to Least Concern in 2014.

The experts don’t know whether the population is stable or falling and they don’t know whether it is fragmented or not. So, the assessment is speculative in my view.

As at 2002, the authoritative authors of the well know book, “Wild Cats of the World” (published 2002), say that the status is unknown. Unfortunately, people have a tendency to exploit nature and this was the case in the 1960s in Pakistan (the Nushki area – see map below and above) when this wildcat was discovered in Pakistan. No sooner had the discovery taken place and several cats captured (attesting to the then high population of this species) there was mass exploitation by trappers, which appeared to have decimated the population leading the government to react belatedly and ban the export of sand cats. By early 1973 this order was hardly necessary as it was all but impossible to find one!

After exploitation and persecution as mentioned (although the fur is not commercially very viable it seems) the following are the major threats:

- habitat degradation (and occupation?) by human activity. I suspect that as the sand cat’s home is the desert its habitat cannot be destroyed as is the case for the forest dwelling cats (logging) but it can be ruined (from the cat’s viewpoint of course).

- natural changes in weather (e.g. snow covering for long periods and drought).

- feral cats, dogs and other predators and due to disease transmission.

- conflict with farmers. The sand cat likes chickens. Traps are set for any animal poaching chickens.

- Note: the Saharan nomads who I believe are Muslims respect the sand cat as tradition has it that it was a companion to the prophet Mohammed.

As to conservation it is admitted by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™, that more work is needed on distribution (meaning where the cat is) and its density in those areas. So it would seem that we don’t have good control over conservation. However, for what it is worth it is listed under CITES II (this is probably more a technicality, in all honesty) and hunting is prohibited in a number of countries including, Pakistan, Niger, Iran, Algeria, Israel, Mauritania and Tunisia. That of course excludes some countries where the sand cat is found including Turkmenistan.

CITES Appendix II:

Appendix II lists species that are not necessarily now threatened with extinction but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled

There are also a number of reserves in which the cat can find protection. For example the Ahaggar National Parks in Algeria:

Map (modified by adding English language) from Wikimedia Commons file (Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported). Thank you.

Sand Cat – Behaviour, Social Organisation, Reproduction

As the name suggests this cat prefers sand rather than clay and/or compacted ground because, in part, in likes to enlarge the burrows of other animals such as the gerbil or occupying abandoned burrows. Also, this kind of territory supports sparse vegetation and small rodents. One was found to be occupied by a sand cat and 5 gerbils! I presume this was time-share. These burrows can be quite large at 3 metres long and have single entrances. The sand cat lives in tough conditions of very high and very low temperatures (above 40°C to lows of -25°C). The burrow is a necessary retreat during the worst of the conditions. Sand cats like to spend some time at the entrance before resting up.

This resilient wildcat travels far from its burrow when hunting, which usually occurs at sunset and continues throughout the night until dawn and early morning. Over this time the cat can travel distances up to 10 kilometres, a prodigious distance for a cat this small. Accordingly, their home ranges are large (e.g. 16 km² and up to 40 km² in Saudi Arabia).

Being an opportunistic hunter (brought about no doubt by the difficult conditions under which this cat lives) the sand cat will take whatever prey is available, which is dependent on where the home range is. Some examples:

Sand cats have big appetites. In captivity one cat was feed 15 mice and would have eaten more if given them. Normally they eat about 10% of their body weight per night. Perhaps a good proportion of this is burned off on hunting, judging by the distances travelled to find prey.

As to communication, this wildcat makes many of the sounds of the domestic cat but some are peculiar to the this cat. For example, they bark somewhat like small dogs. It is a sharp repeating call. It is used, it seems:

- for males seeking males

- for females and males when meeting

The sand cat has a hiss that has a click attached to it: Sand cat hissing

There is also a gurgle that is used when in close contact. In addition there are the usual non-vocal calls such as leaving claw marks and urine spraying.

Reproduction:

| Event | Figure |

| Estrus (oestrus) – sexually receptive or in heat | 5-6 days (estimated) |

| Gestation (pregnancy) | 60 days (estimated) |

| Litter size – mean (small sample) | 3 – birth is seasonal – born in April (Turkmenistan) |

| Weight kittens at birth | 39-80 grams |

| Appearance at birth | Pale yellow or reddish grey fur with small brown spots that are joined |

| At 5 months of age | 3/4 adult size |

![]()

From Sand Cat to Wild Cat Species

Sources:

- Wild Cats of the World

- IUCN Red List

- findarticles.com

- Wikipedia

- YouTube

- Big Cat Rescue

Photos: Published under Attribution 2.0 Generic creative commons license.